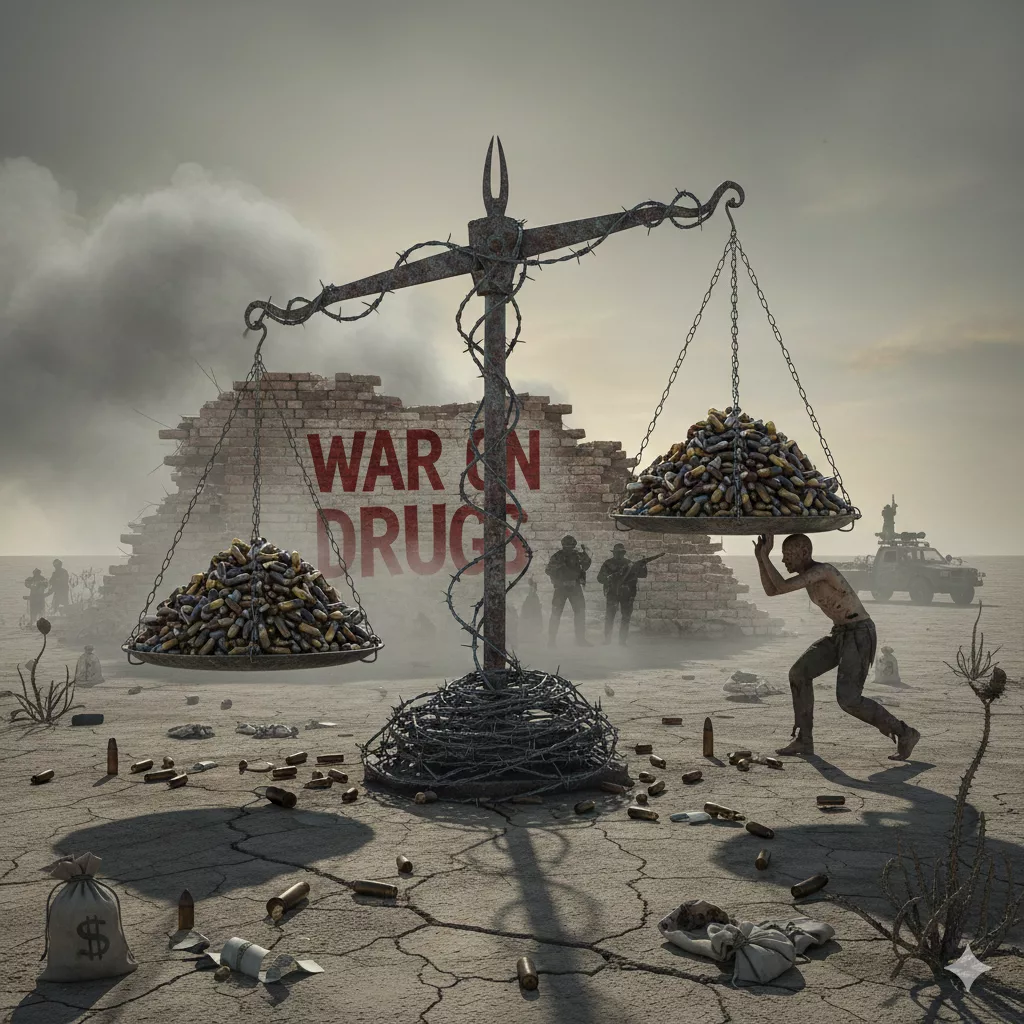

Day 77/100 War on Drugs

War on Drugs

Stormin’

- https://www.lewrockwell.com/2026/01/no_author/u-s-claims-western-hemispheric-domination-denies-that-russia-has-legitimate-security-interests-on-its-own-border/

- I often wonder what Tocqueville would think about America if he travelled the country today. I’m confident he would be hard-pressed to reconcile the extreme malaise—both physical and spiritual—of the American people and their cities with the extreme confidence of their leaders that the United States should rule the world.

- The Maxims are a reflection on our boundless capacity for self-deception, self-serving conduct, and virtue-signaling. The following are some of my favorites.

- “We are so accustomed to disguise ourselves to others, that in the end, we become disguised to ourselves.”

- “We confess small faults only to convince people that we have no greater ones.”

- “We are strong enough to bear the misfortunes of others.”

- “The extreme pleasure we take in talking about ourselves should make us afraid that we may scarcely be giving any to our listeners.”

- “Everyone complains of his memory, and no one complains of his judgment.”

- “We would frequently be ashamed of our good deeds if people saw all the motives that produced them.”

- “No people are more often wrong than those who will not allow themselves to be wrong.”

- “If we had no faults we should not take so much pleasure in noting those of others.”

- “Quarrels would not last long if the fault was only on one side.”

- “One cannot answer for his courage when he has never been in danger.”

- “A true friend is the greatest of all blessings, and the one that we take the least care of all to acquire.”

- Rochefoucauld and Tocqueville would have doubtless remarked that the American people should do something about their own monstrous addiction to narcotics and stimulants before they self-righteously fulminate against the depravity of their suppliers.

- https://www.lewrockwell.com/2026/01/no_author/the-greatest-health-revolution/

=====

Why the U.S. keeps the “war on drugs” approach (even though drugs are still everywhere)

A few forces keep it going, even when outcomes look disappointing:

- Politics and “tough on crime” incentives. For decades, being seen as “soft on drugs” was politically risky, so punishment-heavy policy became the default path. (Nixon’s “war on drugs” framing dates to 1971 and it helped shape federal enforcement agencies like the DEA.) (Drug Policy Alliance)

- Institutional momentum + budgets. Whole agencies, task forces, grant programs, and local police units are funded and organized around drug enforcement. Those systems don’t unwind quickly. One example: Byrne JAG is a major stream of federal criminal-justice funding to states/localities. (Bureau of Justice Assistance)

- International treaty framework. The global drug-control treaties (notably the 1961 Single Convention) strongly shape what “full legalization” can look like at the national level, because they limit certain drugs to medical and scientific use under the treaty system. (UNODC)

- Real public harms (overdose, fentanyl, disorder) create pressure for crackdowns. Even when the strategy “fails” to eliminate supply, crises drive demands to “do something,” and enforcement is the quickest visible lever—especially when treatment capacity is limited.

You’re also pointing at an uncomfortable truth: availability inside prisons/schools shows the limits of supply suppression—high demand + profitable black markets adapt fast.

How many prisoners are in for drug-related crimes?

It depends on whether you mean drug offenses as the primary charge (possession/trafficking, etc.) or anything “drug-related” (crimes driven by addiction, money laundering, weapons tied to drug markets, probation/parole violations, etc.). The cleanest published numbers are for drug offenses.

Across all U.S. incarceration (prisons + jails + other custody), drug offenses account for ~366,000 people.

Prison Policy Initiative’s “Whole Pie 2025” breakdown shows roughly: ~137,000 in state prisons, ~149,000 in local jails, and ~88,000 in the federal system for drug offenses. (Prison Policy Initiative)

In the federal Bureau of Prisons specifically:

- BOP’s live offense table shows ~60,819 people (about 42.8%) incarcerated for drug offenses. (Bureau of Prisons)

- BJS reports that at FY end 2023, drug offenses were the most serious commitment offense for ~45% of federal prisoners (down from ~51% in 2013). (Bureau of Justice Statistics)

So: the federal system is still heavily defined by drug convictions, while state prisons and local jails hold large numbers too. (Prison Policy Initiative)

Have any other countries tried “full legalization” of all illegal drugs?

Not really—no major country has legalized and commercially regulated all currently-illicit drugs for general adult retail sale the way alcohol is regulated.

What has been tried (and is often confused with “full legalization”):

- Portugal — decriminalized possession/use of all illicit drugs (2001).

Personal possession/use is handled as an administrative/public health matter (panels can recommend treatment, fines, warnings). Trafficking and large-scale supply remain criminal. (Americas Quarterly) - Cannabis legalization (but not “all drugs”).

- “Legal access” for high-risk opioids in tightly controlled medical programs (not general legalization).

Countries including Switzerland (and others) have used heroin-assisted treatment in clinical settings for a subset of people with severe opioid use disorder—again, not retail legalization. (ycsg.yale.edu)

1. Possession vs. trafficking: who is actually locked up?

Federal system (prisons only)

Federal prisons are not mainly about simple possession.

- ~85–90% of federal “drug offense” prisoners are there for trafficking, manufacturing, or conspiracy

- <10% are there for simple possession

- Mandatory minimums and conspiracy laws mean low-level roles still get long sentences

In other words:

Federal drug prison = distribution network punishment, not street possession.

State prisons

State prisons look very different.

Approximate breakdown of people in state prisons for drug offenses:

- ~55–60% possession

- ~40–45% trafficking / manufacturing

State law defines “trafficking” very broadly. In many states:

- Possessing more than a small amount = “intent to distribute”

- Sharing drugs with a friend can qualify as distribution

- Addiction-driven possession often escalates to felony status after prior arrests

Local jails (the overlooked majority)

This is where simple possession dominates.

Among people in local jails for drug offenses:

- ~70–75% are there for possession

- Many are pretrial, legally innocent

- Typical stay: days to weeks, but with repeated cycling

This is the real enforcement footprint of the drug war.

2. State vs. federal: why the numbers mislead people

| System | Who controls it | What it mainly targets |

|---|---|---|

| Federal prisons | DEA, DOJ | Trafficking, conspiracy, large cases |

| State prisons | States | Possession + low-level distribution |

| Local jails | Counties/cities | Possession, probation/parole violations, pretrial detention |

So when politicians say:

“We’re not locking people up for possession anymore”

They’re often talking about federal prisons, while local jails keep filling up.

3. Why jails are the real “drug war machine”

This is the part most Americans never see.

Jails function as churn engines

People enter jails for:

- Possession arrests

- Missed probation meetings

- Failed drug tests

- Unpaid fines tied to drug cases

- Bench warrants triggered by addiction-related behavior

Most are never convicted of new serious crimes.

Yet they:

- Lose jobs

- Lose housing

- Lose access to treatment

- Become more unstable and relapse-prone

This is why drugs are still everywhere—including inside jails and prisons.

4. Why drugs are everywhere despite enforcement

You already nailed it, but here’s the mechanism:

- Prohibition creates premium pricing

- Premium pricing sustains corruption and smuggling

- Enforcement removes competitors → strengthens surviving networks

- Prisons concentrate demand + desperation

- Guards, visitors, staff, drones, mail, and medical diversion all become entry points

Prisons are ideal black-market environments, not deterrents.

5. Has any country gone “all-in” on full legalization?

Short answer

No major country has fully legalized and commercially regulated all drugs.

What has worked elsewhere

- Portugal: decriminalized possession of all drugs → shifted resources to treatment and harm reduction

- Drug use did not explode

- Overdose deaths dropped sharply

- HIV transmission collapsed

- Switzerland: medical heroin programs for the hardest cases

- Crime fell

- Public disorder dropped

- Long-term recovery improved

These systems:

- Remove criminal penalties for users

- Keep production and trafficking illegal

- Treat addiction as a health problem, not moral failure

6. Why the U.S. hasn’t followed suit

Bluntly:

- Political fear (“soft on drugs” still polls badly)

- Law enforcement funding dependence

- Private prison and jail contracting incentives

- Treaty inertia

- Cultural moral framing of addiction

- Fragmented healthcare system unable to absorb mass treatment needs

It’s easier to arrest than to rebuild systems.

Bottom line (plainspoken)

- The drug war hasn’t failed accidentally—it has worked exactly as a punishment system, not as a public health system

- Federal prisons punish supply

- State prisons punish addiction

- Local jails recycle human beings

- No country has legalized everything—but countries that stopped criminalizing users have done far better

“Full legalization” (meaning legal production + legal adult access for non-medical use, not just decriminalizing possession) is way more than “make it legal.”

It’s basically building an entire public-health + consumer-safety + market-regulation system for drugs that are currently produced and sold in a violent, unregulated black market.

Here’s what it would actually require in the U.S.—and why it scares policymakers.

What full legalization would actually require

1) Decide what “legalization” even means (there’s a spectrum)

Policymakers have to choose how tightly each drug is regulated. Serious proposals rarely say “everything sold like beer.” They usually propose a menu of models, from most strict to least strict—e.g., prescription-only, pharmacy-style supply, licensed sales, supervised consumption settings, etc. (Transform)

That means: different rules for different drugs (opioids ≠ stimulants ≠ psychedelics).

2) A new national regulatory architecture (like FDA/TTB/ATF—but for drugs)

If drugs are legal, the government must regulate:

- Product standards (purity, dose, contaminants, accurate labeling)

- Manufacturing + supply chain controls (track-and-trace, audits, recalls)

- Licensing for producers, distributors, and retail outlets

- Age limits, packaging, warning labels

- Marketing/advertising limits (this is a huge one—see tobacco lessons)

- Taxes/pricing rules (to reduce black market without encouraging heavy use)

With cannabis, we’ve learned that commercialization and weak guardrails can cause real public health and equity problems—hence major public-health bodies pushing “tobacco/alcohol-style” controls and better surveillance. (American Public Health Association)

3) Impaired driving and workplace safety frameworks that actually work

Policymakers panic here because for many drugs:

- We don’t have perfect roadside tests that map cleanly to impairment

- Employers, unions, DOT, and insurers all demand clarity

“Legal” doesn’t mean “safe to drive or operate equipment,” but the rules get messy fast.

4) Health system capacity: treatment + harm reduction at a much bigger scale

Full legalization isn’t just “let people buy drugs.” A workable model has to include:

- Treatment on demand (not waitlists)

- Medication-assisted treatment access

- Overdose prevention (naloxone saturation, education)

- Supervised use options for highest-risk drugs/users (where politically possible)

Without strong health infrastructure, legalization becomes politically radioactive the first time deaths spike or headlines explode.

5) Criminal justice transition plan

If you legalize supply, you must also decide:

- What happens to prior convictions (expungement, resentencing)?

- What remains illegal? (sales to minors, unlicensed production, impaired driving, exports)

- How to stop enforcement from simply shifting to new offenses (e.g., licensing violations, “drug-impaired” claims)

This is politically loaded because it forces public officials to “own” the transition.

6) International treaty conflicts (the quiet deal-breaker)

The big UN drug treaties require countries to limit controlled drugs to medical and scientific purposes (the core “prohibition” backbone). (UNODC)

That’s why international bodies like the INCB repeatedly say non-medical cannabis legalization contravenes the treaties. (UN Information Service Vienna)

So a country pursuing “full legalization” faces hard choices:

- Treaty reform (slow, diplomatically heavy)

- Legal workarounds (e.g., “inter se” modification among like-minded states) (tni.org)

- Or denounce and re-accede with reservations (a path Bolivia used around coca leaf controls; similar strategies are discussed in legal scholarship) (ResearchGate)

For U.S. policymakers, treaty conflict = “international blowback” + “we look lawless” + “diplomatic cost.”

Why it terrifies policymakers

A) Fear of being blamed for any increase in harm

Even if legalization reduces violence and contamination, if use rises or a high-profile tragedy happens, opponents will say: “You caused this.”

And because the U.S. is dealing with fentanyl and polysubstance overdose waves, officials are extremely risk-averse.

B) “Big Tobacco 2.0” (corporate capture)

Legal markets attract powerful profit-seekers. Policymakers worry about:

- aggressive marketing

- product engineering for dependency

- lobbying that weakens health rules

Public health groups explicitly argue for tight commercialization controls for this reason. (American Public Health Association)

C) The black market might not disappear

If taxes are too high, access too restricted, or prices too high, illegal suppliers keep a foothold. If prices fall too far, heavy use can rise. That pricing tightrope scares legislators.

D) Enforcement agencies and local governments resist

A lot of budgets, roles, and political identity are tied to drug enforcement. Legalization threatens existing institutional structures.

E) Treaty + federalism headaches

In the U.S., you’d have a state–federal collision on steroids (cannabis already shows this). Add “all drugs,” and it becomes a governance earthquake.

Key clarification: “Full legalization” isn’t the only alternative

Many countries that “moved away from the drug war” did not legalize supply. Portugal, for example, decriminalized personal possession/use while keeping trafficking illegal—often confused with legalization. (Prison Policy Initiative)

That model is politically easier because it reduces punishment for users without requiring a whole new commercial supply system.