Day 71/100 Harold Here

Harold Here

Stormin’

- https://www.lewrockwell.com/2025/12/no_author/the-lifespan-of-a-country/

- https://www.lewrockwell.com/2025/12/paul-craig-roberts/americans-who-love-their-country-should-adopt-america-first-as-their-new-years-resolution/

- https://www.lewrockwell.com/2025/12/charles-hugh-smith/everyones-a-lender-now-shadow-banking-usa/

- https://townhall.com/columnists/johnstossel/2025/12/31/doomed-n2668684

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QP9thfJ41rA

=====

This is very common after a long, stressful move, especially an all-day trip and a new environment. What you’re seeing is much more likely stress and fear, not misbehavior. Here’s how to help—calmly and safely.

First: what’s normal right now (first 24 hours)

After transport, many cats will:

- Not eat for 24–48 hours

- Drink very little

- Avoid the litter box

- Urinate in a “safe” place (like bedding)

- Hide, freeze, or seem withdrawn

The peeing in his bed actually tells you something important:

➡️ He was too stressed to move, not trying to avoid the box.

What to do right now

1. Create a small, quiet “safe room”

Do not give him the whole apartment yet.

Choose a bathroom or small bedroom and put in:

- Litter box (open, unscented litter)

- Water bowl (away from litter)

- A small amount of food

- His bed or a towel that smells like him

- Dim lighting, minimal noise

Close the door. This reduces overwhelm and helps instincts kick back in.

2. Fix the litter box situation

Cats under stress are very sensitive.

- Use unscented clumping litter

- Keep the box very close (a few feet away)

- Scoop nothing yet — a little smell helps them recognize it

- If you know what litter he used in NC, match it exactly if possible

If he peed on bedding:

- Wash it thoroughly or remove it temporarily

- Replace with a clean towel

3. Encourage water gently (don’t force)

Dehydration matters more than food in the short term.

Try:

- Fresh water in a shallow bowl

- A second bowl on the other side of the room

- Add 1–2 teaspoons of water to wet food (if he’ll accept it)

- Ice cubes in the bowl (some cats like moving water)

Do not syringe water unless instructed by a vet.

4. Food: less pressure, more temptation

Don’t panic if he doesn’t eat today.

Offer:

- Smelly wet food (tuna-based cat food, not human tuna yet)

- Warm it slightly (10 seconds) to increase aroma

- Very small portions — remove after an hour

No free-feeding pressure. Quiet presence beats hovering.

5. Your behavior matters more than anything

For the next 24 hours:

- Sit quietly in the room

- Speak softly

- Avoid eye contact (slow blinks only)

- Don’t reach, grab, or carry him unless necessary

Let him decide when to move.

What not to do

- ❌ Don’t scold or react emotionally

- ❌ Don’t keep moving the litter box

- ❌ Don’t bathe him (unless he’s soiled and vet advises)

- ❌ Don’t introduce other pets yet

- ❌ Don’t keep checking every 5 minutes

Stress delays recovery.

Timeline to watch closely

Normal stress response

- Peeing resumes in litter box within 24–36 hours

- Drinking improves first

- Eating follows

⚠️ Call a vet immediately if:

- No urination at all for 24 hours

- Straining or crying while trying to pee

- Lethargy + hiding + no water

- Vomiting

- He’s a male cat (especially important): urinary blockage can become life-threatening fast

In Tampa heat, dehydration risk is higher, so err on the side of caution.

A calming extra (optional but helpful)

If available:

- Feliway diffuser or spray

- A worn T-shirt from your daughter in his bed

- Classical or quiet ambient sound

Bottom line

Your daughter’s cat is likely saying: “I survived something scary. I need quiet, time, and safety.”

Give him one small room, calm energy, and 24 hours.

Most cats settle faster than you expect once the world stops moving.

=====

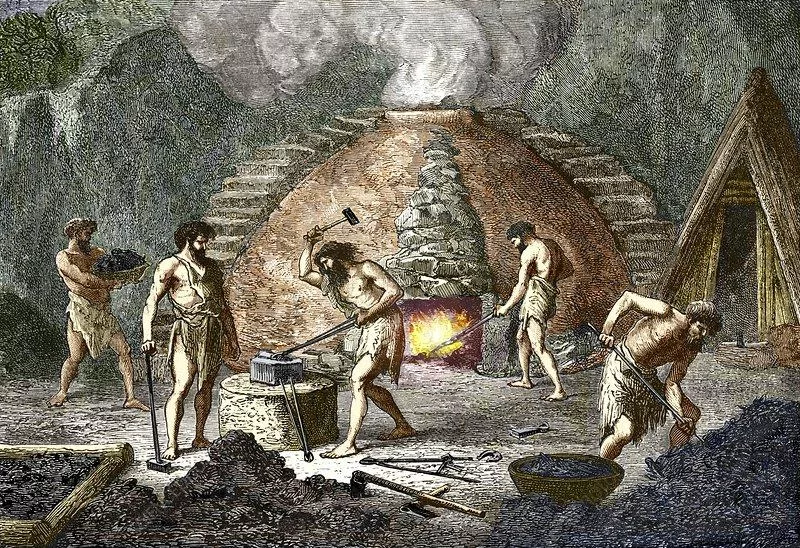

Humans didn’t suddenly “invent” metallurgy. Learning to mine and manage metals like gold and iron was a long, step-by-step process driven by observation, experimentation, and necessity. Here’s how it likely unfolded.

1. Discovery through nature and curiosity

Native metals came first

Some metals appear in nature in pure form, especially gold and copper. Early humans encountered them as shiny, unusually heavy stones in riverbeds or exposed rock.

Gold in particular:

- Does not rust or corrode

- Is soft and malleable

- Can be shaped by hammering, no fire required

This made gold humanity’s first workable metal. People learned it behaved differently from stone and bone—bending instead of shattering.

Pattern recognition

Over generations, humans noticed:

- Gold often appears near rivers and eroded hills

- Certain colored stones yield copper when heated

- Fire can permanently change materials

This observational learning was crucial. Metallurgy began as applied curiosity, not theory.

2. Fire, ceramics, and the leap to smelting

Kilns before metals

Before metalworking, humans already mastered:

- Pottery kilns

- Charcoal production

- Controlled high heat

These technologies made smelting possible. Heating copper ores in a charcoal fire accidentally produced molten metal—an extraordinary discovery.

From hammering to smelting

This marked a huge shift:

- Cold working → shaping native metals

- Hot working → extracting metal from rock

Copper tools were softer than stone, but reusable and repairable—an early trade-off humans learned to manage.

3. Mining: learning to read the land

![]()

Surface mining first

Early mining focused on:

- Exposed veins

- River sediments

- Soft rock

Tools included antlers, stone hammers, and wooden wedges soaked in water to crack rock.

Over time, miners learned:

- Which rock colors signaled metal

- How veins follow geological patterns

- How to ventilate tunnels with shafts and fires

This knowledge was practical, local, and passed down orally.

4. Iron: the hardest lesson of all

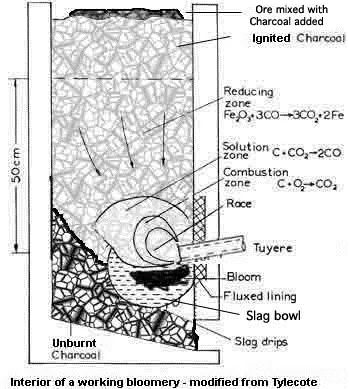

![]()

Iron was a much greater challenge than gold or copper.

Why iron came later

- Iron ore requires much higher temperatures

- Iron doesn’t melt easily—it forms a spongy bloom

- Working iron demands repeated heating and hammering

The breakthrough likely occurred in regions like Anatolia, where skilled metalworkers experimented with hotter furnaces and better charcoal.

Iron’s advantages:

- Stronger than bronze

- Widely available

- Ideal for tools, weapons, and farming

Once mastered, iron transformed societies.

5. Management: metals reshape society

Specialization and trade

Metallurgy created new roles:

- Miners

- Smelters

- Smiths

- Traders

Metal knowledge became guarded expertise, sometimes sacred or state-controlled.

Feedback loop of progress

Better metal tools → better mining → better furnaces → stronger tools.

This self-reinforcing cycle accelerated technological growth.

6. The deeper truth: learning by doing

Humans learned metallurgy the same way they learned everything else:

- Trial and error

- Careful observation

- Intergenerational knowledge transfer

No blueprints. No chemistry textbooks. Just hands, fire, time, and attention.

Gold taught humans beauty and symbolism.

Iron taught them discipline, heat control, and patience.

Together, these metals helped move humanity from the Stone Age into complex civilization.

======

Japan’s metallurgy followed a different path from much of Eurasia—later in time, more isolated geographically, and shaped by scarce resources. That combination is precisely why Japanese smiths developed some of the most refined blades in human history.

1. How metallurgy reached Japan

Late arrival, rapid mastery

Metalworking arrived in Japan around 300 BCE, during the Yayoi period, via cultural transmission from the Asian mainland (Korea and China). Early metals included:

- Bronze (mirrors, ritual objects)

- Iron (tools and weapons)

Unlike regions rich in copper or tin, Japan had limited metal ore, which forced innovation rather than abundance-driven use.

2. Japan’s unique iron problem—and solution

No good iron ore

Japan lacked large deposits of high-quality iron ore. Instead, smiths worked with iron sand (satetsu), scattered through riverbeds and hills.

This sand was:

- Impure

- High in oxygen

- Difficult to smelt

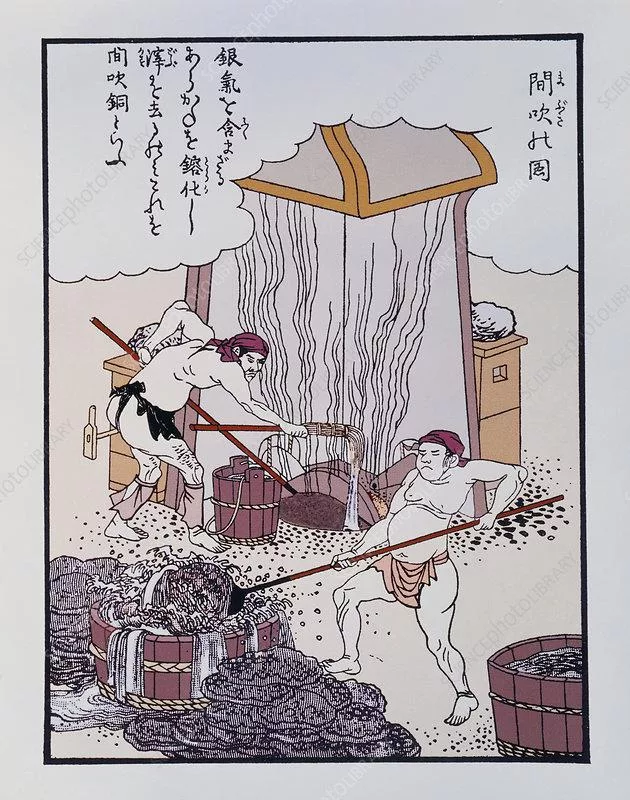

The tatara furnace

Japanese metallurgists developed the tatara furnace—a clay box furnace operated continuously for several days.

Key innovation:

- Careful control of charcoal, airflow, and timing

- Producing tamahagane (“jewel steel”)

Japan’s metallurgy didn’t aim for mass production—it aimed for selective excellence.

3. Why Japanese steel was special

Natural steel grading

A single tatara smelt produced steel with multiple carbon levels:

- High-carbon steel (hard, sharp)

- Low-carbon steel (tough, flexible)

Rather than seeing this as a flaw, Japanese smiths learned to sort and combine steels deliberately.

This insight was revolutionary.

4. The sword as a metallurgical system

Japanese swords were not just sharp objects—they were engineered composites.

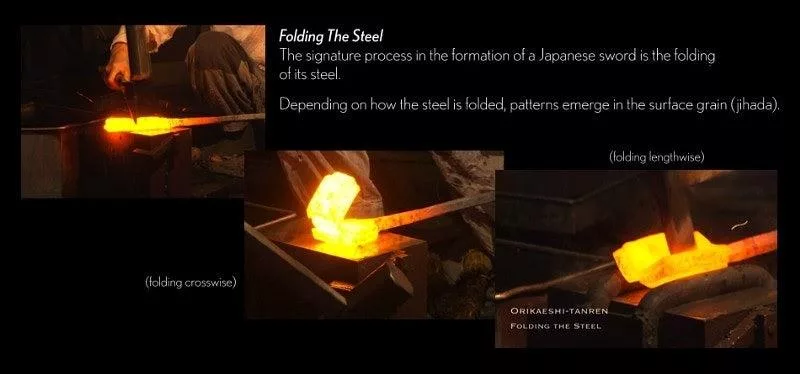

Folding: misunderstood but critical

Steel was folded not to “add layers,” but to:

- Remove impurities

- Even out carbon distribution

- Align grain structure

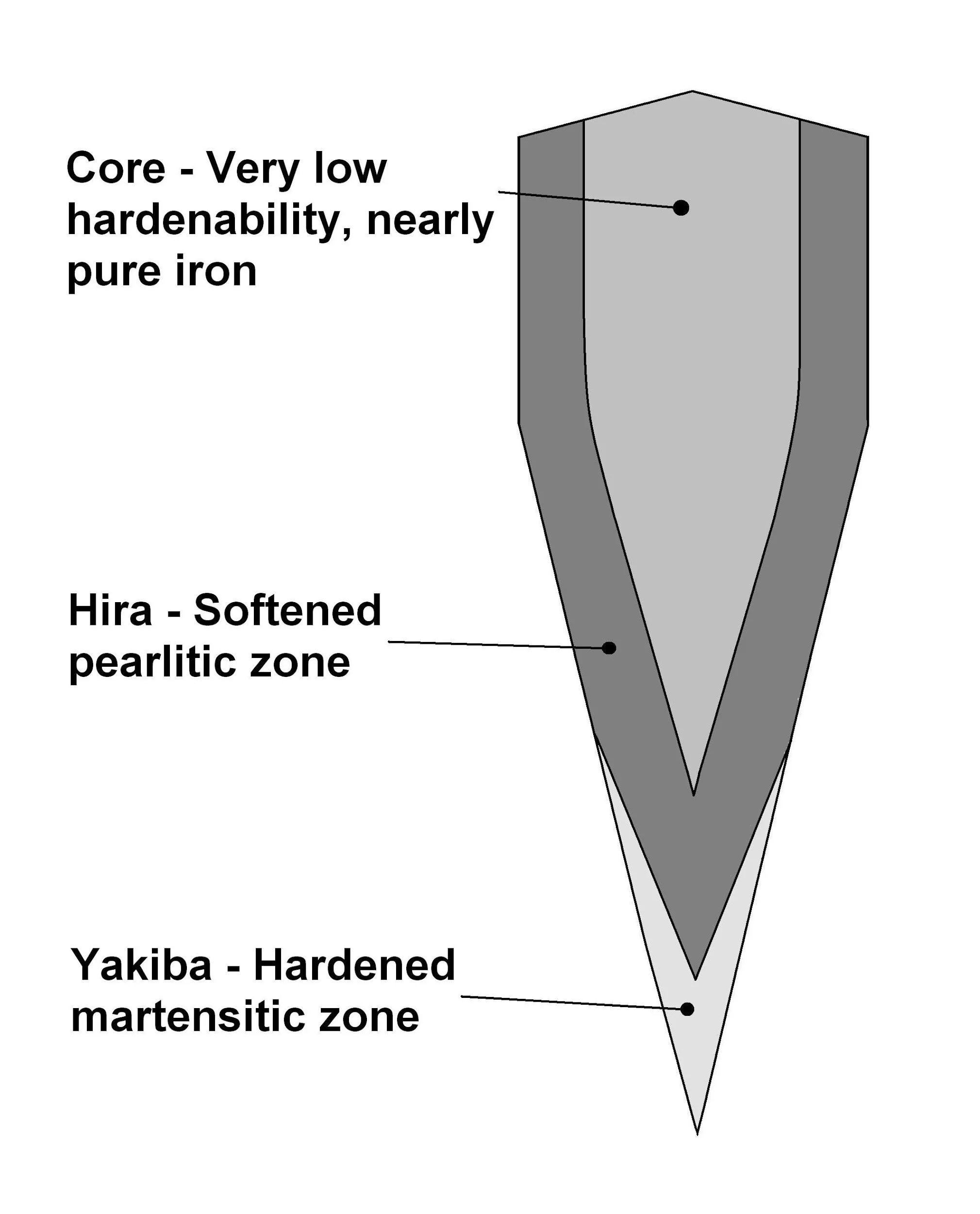

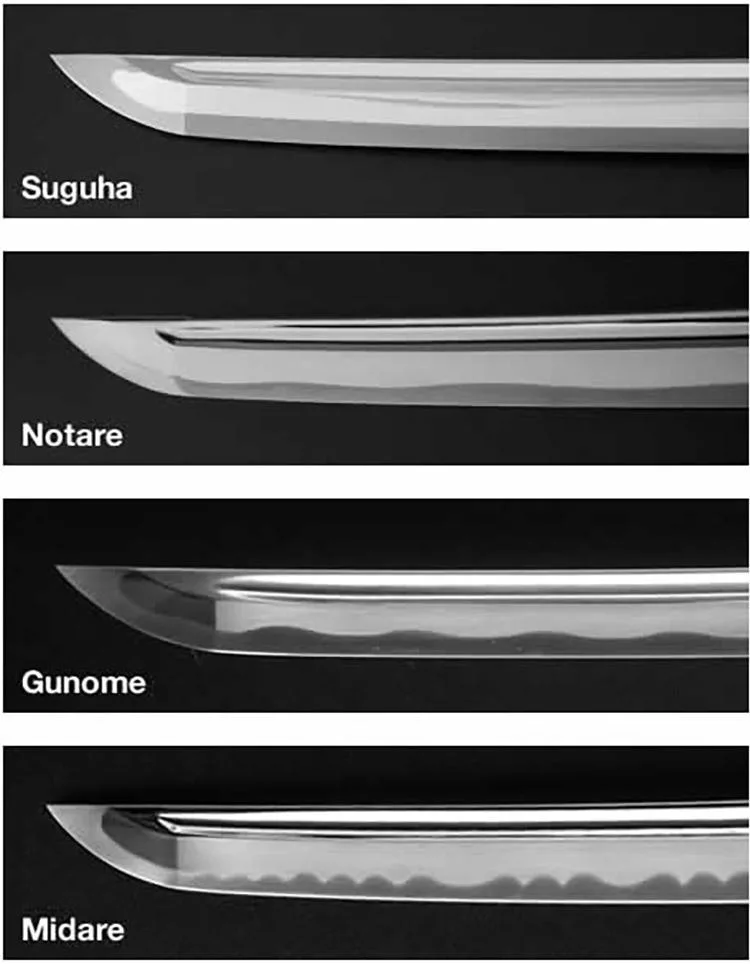

Differential hardening

Smiths coated the blade with clay:

- Thick clay on the spine → slow cooling → flexibility

- Thin clay on the edge → fast cooling → hardness

This created the hamon (temper line), both functional and aesthetic.

Result:

- Razor-sharp edge

- Shock-absorbing spine

- Resistance to shattering

5. Cultural pressure toward perfection

Scarcity shaped discipline

Because steel was precious:

- Mistakes were unacceptable

- Every blade mattered

- Knowledge was guarded and ritualized

Swordsmithing became:

- A spiritual practice (Shinto purification rituals)

- A hereditary craft

- A lifetime discipline

The sword was viewed as the soul of the warrior, not a disposable weapon.

6. Isolation refined excellence

During long periods of limited foreign contact, especially the Edo period, Japanese metallurgy evolved inward.

Without industrial competition:

- Craftsmen optimized technique, not output

- Subtle improvements accumulated over centuries

- Aesthetic refinement matched functional mastery

This is why Japanese swords are admired not just as weapons, but as metallurgical art.

7. Why they became “the world’s best”

Japanese swords excelled because of:

- Necessity – poor raw materials demanded ingenuity

- Process control – mastery of heat, carbon, and timing

- Composite design – hard and soft steels working together

- Cultural reverence – craft elevated to moral discipline

They were not mass-produced killing tools.

They were precision instruments shaped by scarcity, patience, and meaning.

The deeper lesson

Japan didn’t win by having better resources.

They won by paying closer attention.

If you’d like, I can:

- Compare Japanese swords to European or Middle Eastern blades

- Explain why katanas were not ideal battlefield weapons but perfect dueling swords

- Or connect this to your Phoenix72 themes: scarcity, mastery, and disciplined simplicity

=====